I went to a Christian high school based in the Calvary Chapel movement. In some ways, being a leader in that evangelical environment for four years was more formative for me than my decades in the Church of Christ. I remember, during confession time with just the teen girls and our teachers, one of my friends confessed to being worried she was attracted to girls. My thought was, huh, I had no idea and I cannot relate to that in any way.

Read MoreShe's on Her Way

I had an unexpected reaction to being a one-person support staff for Macy’s senior photo shoot on Sunday. I had our wagon with the makeup, outfit changes, lint roller, etc. As we wheeled to the first area of the park, we passed the playground. There were toddlers everywhere.

My body went right back. It was like rewinding an old VHS tape. I’m immediately there. To all those afternoons in the grass. So many viewings of Finding Nemo. Big belly laughs. A million frozen blueberries after we picked them for the first time. Reading side by side (we still do this on occasion).

People say we look alike. We joke that we just have similar taste in glasses.

She has always been herself. From that first day of kindergarten where she left with her chin up and did not look back, I knew. She dressed herself in wild patterns in preschool and I did not say a word.

We go to the first site and the photographer is checking light. We’re laughing. She looks beautiful, and young. This is her first look and it’s meant to be a little youthful. She’s so beautiful, I can barely look at her. My heart is bursting.

I begin texting my best friends. I’m freaking out. It’s too much. The beauty is overwhelming. Guys, I was not prepared for being in my feelings! I was thinking about logistics.

We hustle to the bathrooms because my girl does not want to change behind blankets we hold up. Her next look is more how she feels now, her theater self. It’s more modern, whimsical. We purchased a quill and leather-bound book for the occasion. We head to the garden. More laughter. Our photographer pays me an unexpected compliment. It registers with kindness.

We’re in a field. We’re mentioning the cool feature on the back of the dress. She’s natural. We even see her teeth in a few shots. We’re having fun.

She’s so composed. She’s always been a serious person. I respect her so much.

We race back to the bathroom for the final look. It’s more edgy. The most adult. Our photo shoot is running over time. Should I pay her more? I brought cash in the exact amount plus tip. Shoot.

We walk down the lane where we took family pictures two years ago, where we will be again in a few weeks the three of us. But tonight is about just one person. This person who is becoming. I’m watching this shot be taken and I think, my God, she is a woman.

Yes she is wearing my clothes and we’re still working on driving, but she is a woman. I text my friends, when did this happen?!?

I see her childhood dimples and her first audition at eight years old. I see her face disappointments and still celebrate those who got what she wanted. I see her rolling her eyes at her sister, and learning how to push back in our relationship. I see her. I see her. I see her.

In all our primary relationships, we project. I saw this so clearly when I left my long-term marriage. We project so much onto people we care so deeply about. It’s normal. It’s inevitable. It is tragic.

I want to see her so clearly. I have always wanted that. And I know, too, that no mother ever fully witnesses her daughters clearly. We see them and there are hidden parts. This is part of it. But my God, have I tried to witness. And I will keep trying. Forever.

She’s always belonged to herself. And that remains.

I cannot describe how incredibly beautiful it it to watch a woman become. I see every version of her I’ve known. I imagine future versions of her, God willing. And I adore every. single. one.

I can’t help but imagine that this might be how God sees us. And how we must see ourselves. I’ve spent the past few years really adoring old versions of me. Versions who were afraid of her own power. Versions that loved so hard and tried too much. Versions that meant well and were so terribly wrong. I see her. I see her. I see her. I love her. Look at her become.

If God is outside of time, can they see us in all our versions at the same time? Is mothering the closest thing to God?

I know I’ve never loved anyone as much as this child. And I know I never will. (and of course, her sister, too).

I don’t parent from a sense of who I think my kid should be. That never made sense to me - to the point, that I’ve always been clear that I have no idea who my kid should be. I love her hard and I try to live my life in integrity. I give her access to supports and community that I think she may enjoy. I feed her and hug her. I listen to know her well. That’s it.

All of that to say, I fucking cherish her beyond all else. The beauty radiating from her on Sunday is so much more than youth and actual physical beauty. She is wise. She is grounded. She is powerful. She’s fucking magic.

I live with a lot of privilege. My job reminds me every single day what a gift it is to do it. But the greatest privilege of my life has been standing on the sidelines watching these kids as they become. My God, what a gift.

I hate greed

I’ve been feeling down lately. I was talking to my friends about this recently, as low energy and low motivation is pretty rare for me. I realized that everything going on politically is wearing me down. I’m barely even engaging in it and I’m still wiped. I spent some weeks in abject panic and anxiety.

And now I’m flat. But not irretrievably flat. I began to cry talking about it, so I’m not totally gone. But the conclusion I came to is that I do not understand greed. I do not understand why anyone would want to have power over the lives of others in an exploitative way. I do not understand the impulse to take more than is mine. And granted, I’m a very privileged person living in a very privileged country when you speak of global access to resources. I understand that I already take more than my fair share of clean water, electricity, and fuel.

In this case though, I’m speaking of men who have a pit within themselves that no amount of money or power can ever fill. Ever.

I imagine that feels like shit. Not to ever be satiated. To never feel comfortable when all the artifice falls away, when your nakedness is exposed, and you feel safe, good, precious. I can see by their behavior that they don’t have that. They could have that, if they’d put down their bravado, stop shouting, and be vulnerable. But they won’t.

And that would be okay if it didn’t ruin the world and everyone in it. Everyone who has done their sacred work of self-compassion, those who have worked hard to build community, and frankly, just those who are alive and deserve basic rights and dignity. We don’t need to be saints to be essentially sacred beings.

I feel disgust. I am enraged. And I am so damn tired.

And I feel silly for saying that because justice work and resistance has been going on for centuries longer than white folks ever realized. Because we didn’t have to. And most didn’t/don’t want to. I’m new to the conversation. Maybe that’s why I’m less resilient.

I’m sorry that’s not bolstering for others to read. I really am. I want to be the kind of spiritual leader who rallies everyone together, who leads the charge to fight against racism, xenophobia, misogyny, transphobia, and fascism. And I do fight those things in my own way - uprooting the seeds planted within me by this culture, seeing the people around me and responding, being emotionally available, and doing concrete justice work here in Portland.

But I also feel a little lost and a lot scared. I’m so angry.

I hate greed. I do not get it. How are we still doing this as human beings? We keep doing the same shit over and over. The devastation of a few men’s greed is catastrophic. And yet, here it is again. When are we going to stop letting men who must have everything take over so no one else has anything?

Sometimes I wish I was less sensitive, less attached to the outcome. It might be nice to care a little less. I have tried to have boundaries around how and when I consume media right now. But it seeps into my bones, my very spirit.

I wish I had a shiny happy conclusion to write. I’m low and for now, I’m listening to whatever the low wants me to know.

Living Memoirs

I love reading memoirs. I don’t know if it’s because I’m a youngest child, but I have always loved hearing what those who’ve gone before me have learned. Now that I’m older, it’s not so much for the purpose of avoiding pitfalls that others have experienced. It’s more like, savoring the humanness in others has taught me how to savor the humanness in myself. There is something so precious about how much we mess up, how hard we try, and how often things just don’t go the way we hoped. Life is so incredibly hard. And I have come to understand that achieving the goal that so many of us say we want, living to a very, very old age, is not what young people think it is. I think our highest rate of suicidal ideation is probably in those that are near or over 100 years old. Not because they haven’t lived a good life, but that all the good in life is behind them. They can’t taste or see or hear or walk or breathe deeply…all that brings joy is hard to access and everything is just so damn hard. I didn’t realize that until I started spending time with the uber elderly.

I realized the other day, that my job is like listening to a memoir in real time. People spend time doing life review at the end of their lives. Often in hospice, people are medically past the point where they are able to engage in this developmental practice, but not always. We take an inventory of what our life has been, catalog our regrets, review for what we are most grateful, and savor the beauty we’ve experienced. This is normal in old age and especially supportive of anticipatory grief work when facing death. Sometimes there are things that must be said or done. Most of the time, it’s simply held.

I was with a patient recently who has a historical relationship with meth. Her life reflects this – subsidized housing, no support system, estranged family, a friend who identified as a “caregiver” and then stole her hospice meds, lives alone…you get it. The other day, I was sitting on her couch that is nowhere near clean and I simply don’t care. I am petting her cat wondering if I will be bringing anything home to my cat from this one, but he’s so darn cute and soft. I breathe the stagnant air while she smokes and vapes (I’m supposed to tell her not to but I don’t). We openly talk about death and she said she’s planning on going to purgatory and then becoming a ghost. I said, “oh, I didn’t realize you were Catholic.” (these are the things I’m supposed to know). And she said, “oh, not like that purgatory. I’m going to pay some people back for all the wrong they’ve done me.” Ah. Slightly different interpretation. How delightful. She has been wronged many times, for sure. So we talked about our human need for justice, to have our harm be acknowledged, and how often that simply does not happen in this life. We laughed about the absurdity of knowing death is coming and not being able to do anything about it. It is kind of wild that we’re animals but we know so much more than all the other ones do. Awareness is not always a gift. Existential crisis, indeed.

I put her groceries away, handed her some M&Ms I found, updated her social worker, and wished her well, knowing that she’ll probably have to die in the hospital because there will be nowhere for her to go once she can’t get up on her own. That’s not really our preference in hospice, but what can we do? There isn’t a place for her. But there will always be a place for her, and for so many others, within me. Because the chaplain gets to be the keeper of the stories, the witness, the secret holder. And I cherish this so.

Sometimes people cry or say the truth to me in ways that are not socially acceptable. They apologize or say “oops I didn’t mean to say that out loud” like it’s an unusual thing. But of course, it’s not. We all need places to put the truths we feel we cannot acknowledge or should not say out loud. But what better place to put them than within the soul of another. We speak of relief when someone dies or disappointment when they don’t and this process just goes on and on. We feel judgement for our loved ones that simply won’t let go. And we feel the burdens, but we’re not supposed to ever say that caregiving is a burden. But can a burden be heavy and still be willingly carried? Yes. I think it can.

We live in a culture that so desperately wants to be independent, autonomous, self-determining. And yet, that doesn’t really work for us. Certainly not when we’re dying. For some of us, needing care is the worst possible outcome. It is so deeply painful to feel overwhelming need, even when the need is so lovingly addressed. Sometimes especially so. The role reversal of a child caring for a parent is sometimes too much for both sides of the situation. It feels undignified, or like it’s a life without quality. And yet, I can’t help but see that we come into this world totally dependent and if we’re lucky enough to not die tragically, we probably will leave this world totally dependent as well. So what is our relationship to our own needs? And can we be kind to ourselves when they are so very big? (I’m speaking to myself, by the way).

There are so many gifts I receive from spending my days with the dying. But one of them that strikes me so often is that my work is to help others be kind to themselves as they wither away. The slipping of power, will, ability that just moves without consent. Sometimes the slipping is rapid, in one fell swoop and other times, it is gradually further and further away every day. Some people are so relieved. They just set it down and walk away. And others are just desperate for every moment. And of course, many things in between. None of us really know what happens after we die. For some, that’s okay or even feels like an adventure (I once had a patient eat a hearty meal before taking his Medical Aid in Dying medications, “to fortify for the trip” to whatever comes next. I found that to be so tender and cool.) Others, especially those raised in fundamentalist religions, find this quite terrifying. And once again, everything in between.

Perhaps the greatest gift is that I live my life every day in light of the fact that it is temporary, that the present moment is all we have, and that living in integrity and kindness is the way I want to be no matter what. And to have that clarity and the courage these past few years to walk that out, in the middle of my life instead of at the end, is a gift the dying give me every single day.

We’re living in harrowing times. We don’t really know how bad things are going to get. How will you be in relationship with others? Will you be kind to yourself? Will you live your values no matter what?

By the way, I’m officially a reverend! Seemed like a funny time to finally tie that bow (two days before inauguration), but I wouldn’t change the timing for anything. I am so grateful for the years that led me to that moment and for the brevity of the moment itself.

I Have a Thing About Time

I’m not sure what it is, but I’ve always been a pretty serious person. I recognize that life is both short and long and that all we have is the present moment. I was nostalgic even in elementary school. Yet, I have this other thing, where when it’s time to let something go, I really do. It’s a process to sift through, which was the impetus for creating this blog 10 years ago, but I release things initially pretty well and sort as I go. It’s a weird dichotomy because I imagine most people who are nostalgic also probably struggle to release. My ability to release has also grown quite a bit since I started my chaplain training.

Spending time with the dying has really brought this mindful part of myself into sharper focus. It’s a developmentally appropriate practice for the dying, if they are able to reflect, to engage in life review. Many people feel a sense of peace about the life they’ve lived, the relationships they’ve had, the work they offered. But sometimes people don’t. They have deep regrets. And it is in the privilege of holding space for the misery that is deep remorse with no way of going back, that I am even more committed to living my life as authentically as I can.

I left a long marriage. Every marriage is its own ecosystem. No one else knows what it is like to be in someone else’s marriage, even one you witness well. Not even the two people in it have the same experience. The relationship is shared, but the experience is still unique to the individual. Divorce is the same. Each person has the story of how and when and why it didn’t or couldn’t continue. And that is valid, because it is the story we create to cope. It is a tornado of loss, even when it is right. I have been so empowered by my decision to divorce. And it is fully in line with my values and my desire to live authentically.

We all live in the stories we make out of our lives. And at the end of it, we get to see if we think it was a good one. The fact that I get to sit in the room where this sacred work happens, and even more so, in the active stage of dying, where someone is leaving this life and moving to whatever is next, is such a tremendous privilege and responsibility. Learning when to touch someone and when to be still, recognizing when someone is doing their work of letting go that is not to be disturbed…I call it watching someone pull up their tent pegs. If we’re lucky enough to die gradually, as opposed to traumatically or suddenly, we go through a process where we pack up our bags. This is all happening on a spiritual plane. We release our people. We let go of all that is being left undone. And we rest.

We are embarking on a difficult time in this country and in this world. So the question is, what will we do with our one wild and precious life? How will we behave as structures in our country are threatened, as human rights are rolled back? I’ve been in a time of grief and reflection and the conclusion I’m coming to is that I want to double down on all the values I already live. If I have stuff in my car for houseless people, I’m doubling up. If I make donations to civil rights work, I’m increasing that payment. If I am part of creating and leading a congregation of marginalized people, I’m there every day I can join. If I have access to things other people don’t, I’m making sure I can have things to give away to facilitate greater access. This is the time to lean in.

No one knows the future. But I know who I want to be in it.

Hospice is Sad, Y'all

Maybe this is the most obvious thing I’ve ever written, but hospice is sad, y’all. I’ve started working in hospice as a chaplain. It is so cool to learn a new context for my skills and to build a more well-rounded skillset with every job I take. I thought I was pretty well prepared to spend so much time with death. Having done my internship and residency in a level one trauma center during Covid, getting a divorce after a 17 year marriage, and then doing a fellowship in palliative care at the VA (often a precursor to hospice), I kind of thought I was pretty comfortable around death. Turns out, I am. I have come to see death as a friend. I have totally upended my life in light of my experiences around death these last four years in chaplaincy. So much of the life that I am building now is in light of the fact that all of us are temporary.

Read MoreBeing Present with Myself

I’ve been working on and through so many things in the last few years. Doing 6 units of Clinical Pastoral Education back to back (a year of residency followed by a year of fellowship) led me down many personal paths of trauma processing, grief work, growth, and integration. Going through my ordination process and a divorce at the same time led to additional depths of pain and healing…

Read MoreIt's Official!

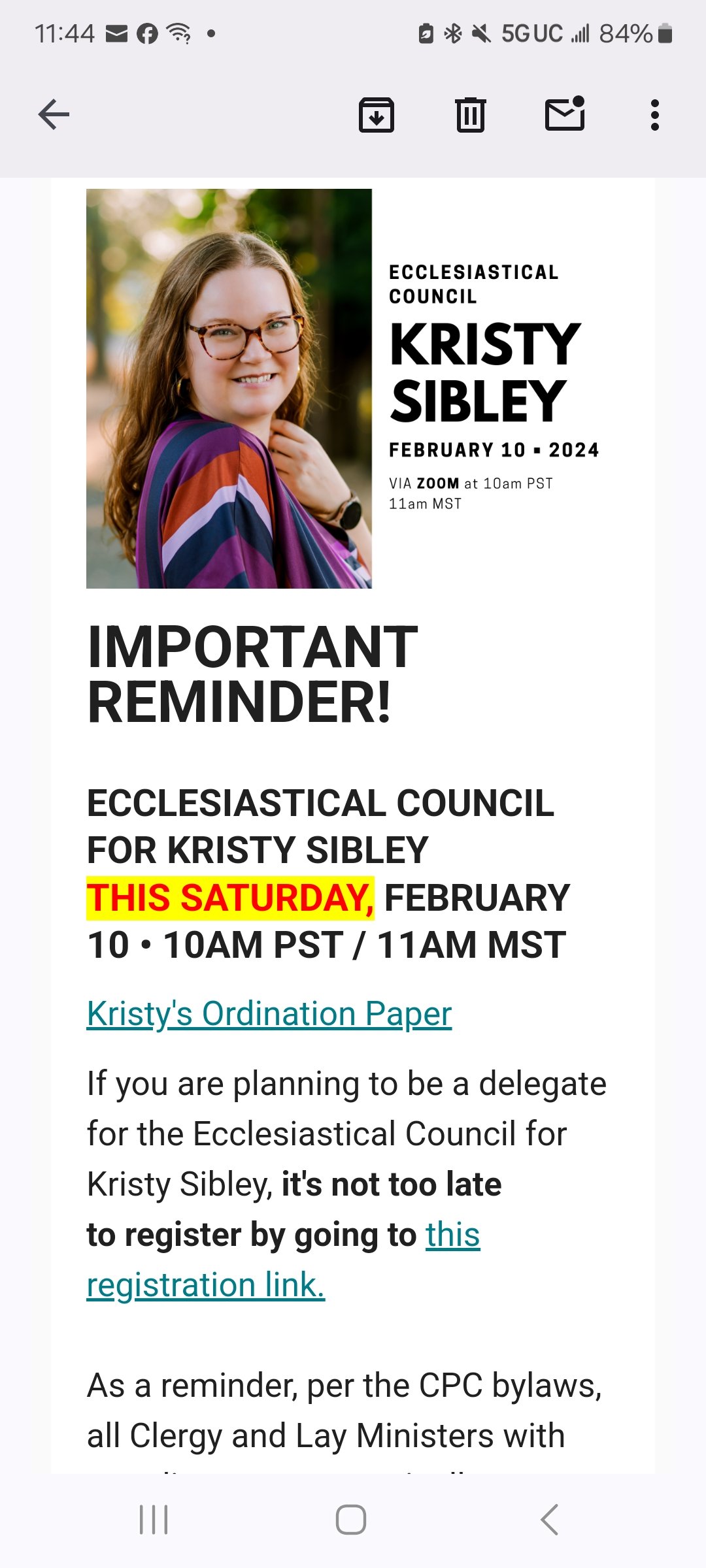

I was approved for ordination today. For those of you not in the know regarding the minutia of this process in the UCC, today was the culmination of 2 and a half years of ongoing work - writing, mentoring, gathering with the committee on ministry and my support team, a 6 hour psych evaluation, and a seminary-level course. It has been up and down. My insecurities and imposter syndrome, my defensiveness whenever I feel pressured to “land” theologically, my need for belonging. All of it made an appearance in the last 2 and a half years. Today was the last hurdle before I get an ordainable gig and plan a service to make it official.

What unexpectedly touched me this morning as I was getting ready, was that today was an affirmation of God’s work in my life since I was 14. I’m 42. When I saw the 50+ faces on the Zoom screen today from 20 something churches in my region of the US, gathered to discuss my 21-page (single-spaced!) final paper, the tears just started falling. Because in 28 years, this was the first time where I was standing before a community of people who were there to witness the work of God in me. I am not a threat to the work of God. I am, in fact, a participant. Of course, that has always been true (and is true of many others). When I was a teen, I received covert help over the years when ministers hoped the elders wouldn’t notice. The years in worship ministry, youth ministry, campus ministry, women’s ministry, children’s ministry, overseas mission work, and now chaplaincy just started scrolling behind my eyes. What a time I have had.

I thought about how much a part of my early connection with my former spouse was about ministry. It was something that brought us together. For a time. We made these beautiful daughters. At some point, he no longer shared that vision. The community agreed with him. I felt left behind. Because my access to use my gifts in ministry were tied to his calling before. Much later, we got divorced. But I wasn’t left behind. Our paths diverged. I wouldn’t be here now if I hadn’t deconstructed that tidy world I lived in then. Huh.

And now. Somehow. I’m going to be able to feed my little girls with money I make. In ministry. As their mom.

I don’t know if it is quantifiable how much having my gender be a determining factor in my qualifications for ministry has harmed me over a lifetime. The scars are there. I have done the grief work and can remain connected to those roots without having them continue to tell me what’s possible.

The faces of all my CPE colleagues - the people who took the time to call me out, to be with me as a grew and cried and integrated so much for so long, were all there. The supervisors. The educators. The patients. The colleagues. The security officers. My professors. My seminary cohort. The friend who gave me my first opportunity to preach. With all of this in my heart, and a feeling of awe in how many people continue to gather around for prayer and witness of God’s continuing work in me, I stepped into the spotlight today.

Wildly, someone from the church of Christ was there. Someone who also sojourned to the UCC. He private messaged me at the beginning - “do I know you? Are you so and so’s wife?” What a small world, y’all. The irony was not lost on me.

I am no one’s wife. But I am a reverend.

Waking Up Surprised

I was leaving the YMCA yesterday and saw a houseless man with one leg in a wheelchair, the other having been amputated just below the knee. He was using his one leg on the ground to propel him forward and seemed to be used to getting around that way as he was not actively struggling with it or seemingly upset.

I’ve worked with so many patients who have gone through amputation surgeries and for whatever reason, this type of loss is one of the ones I am most drawn to support people in. I have been with houseless folks pre-surgery, showing me their black feet (when I say black feet, I mean BLACK feet…this was a new sort dead tissue for me to see before working at an inner city hospital) as a kind of anticipatory grief practice. I knew the next time I saw him, instead of his uncovered black feet, I would see two nubs covered in bandages. We imagined how his life would change, being discharged to the streets without feet. We joked about the difficulties of stealing from stores in a wheelchair when his practice had been to run. The wounds from these surgeries require high levels of hygiene, which is completely impossible in a tent.

I’ve had so many patients at the VA who had undergone these types of losses years earlier only to adapt and come back to us with other health issues. But sometimes the trauma of those losses remained unprocessed. It is a strange thing to lose part of your body.

I bring all of this up to say, there is a certain kind of disorientation that comes from waking up to a new/changed/different body. And though I am unbelievably lucky so far to have kept all my wanted body parts, every once in awhile, I wake up to my very different life and feel a sense of surprise. Surprise that I left my seventeen-year marriage, surprise that I am the only adult in my house, surprise that my house is full of pets, surprise that my life has fully de-centered men in every way. Of course, this feeling of surprise is often followed by a little thrill of excitement and pride.

It seems kind of shitty to even compare this type of total reorientation in life to something as major as losing a foot or a leg. Like, in some ways, saying this is just not cool at all. I’m guessing my houseless friend isn’t feeling thrill when he looks down at his new nubs and bandages. But I think all humans experience grief and disorientation. And the feelings themselves are often so similar even if the details are really different. Maybe he is thrilled to know that he will no longer have to see those black dead feet. I’m not really sure.

Perhaps having a beloved but dead body part excised in order to live a safer and healthier life is not unlike leaving a relationship that has since died* and feels like a weight one can no longer bear. That in leaving behind what is dead, new life is on the horizon. Even if it’s not the life that was imagined and sacrificed so highly to reach for. It’s an opportunity. A new future that is unwritten.

I was raised to believe that divorce is a bad thing. And certainly there is a lot of pain in divorce and it is a hugely destabilizing process for children and adults.

And. Would I tell my houseless friend that it was a bad thing to remove his blackened feet? No. I don’t think I would. There is a quiet dignity in burying our beloved dead body parts and relationships. It is intellectually honest. And it makes room for the spirit to breathe again, to stop the creep that dead tissue sometimes does, invading healthy tissue in a race to win it all.

In many ways, I’ve left behind the binary thinking of good and bad. I’m learning to be in my body, to awaken desire, to FEEL, really feel the full human experience. It is a wild thing to be alive.

*Please know that these comments are specific to my experience and a relational dynamic I was part of and participated in for two decades. This is not a reflection on the personhood of my former spouse.

When Ash Wednesday Fits Like a Glove

For those who follow the Christian liturgical calendar, Ash Wednesday comes 40 days before Easter and commemorates the beginning of the Lenten season. It’s a time to honor the reality that we are mortal. We say things like “Remember you are dust, and to dust you shall return.” While this may seem morbid and even gross as we literally put ashes on our faces, as a Palliative Care chaplain in the middle of a divorce after a 17 year marriage, it could not be more fitting. I am not living a life right now that can ignore loss and sorrow. It is all over my face.

As seems to happen more often than not since the pandemic, my community’s plans had to change as we received an unexpected deluge of snow today and the city shut down. So I self-administered the ashes I swiped from work before I left for home early to beat the anxious Portlanders to the freeway.

I arrived at my quiet and beautiful home, to the stillness that comes on the days my children are with their father, with the communion cup of ashes clutched in my grip to protect them from the falling snow.

I took a nap. I had an orgasm. I ate pasta in bed. I listened to my favorite women on a podcast. Then I hopped on Zoom to see my people and to hold the tender truth in community that we all are dust and will return to dust one day. And, that somehow, this dust is magic. Magic put here on earth, animated and full of life and love and hopes and dreams. We lit our candles, burned our pages, had our communion, anointed ourselves with oil, and imposed our own ashes. We talked for awhile afterwards, checking in on each other, inquiring about the lives of new folks (there are always new folks), and sharing our community’s joys and concerns.

It is a bittersweet thing to spend so much time with death. So many of my friends from work are dying patients. And, we are the only sentient beings as fully aware of our impermanence. We live in this reality we so often would prefer was not true - that everything we know and love and rely on will eventually end. Our very deepest attachments are all temporary.

We can imagine that dust is so insignificant that it just blows away with a small gust of wind, never to be seen again. It would be so easy to think that the dust, that we, are inconsequential. And yet. That is where the magic comes from. This God who breathed life into us, gave us these deeply feeling, deeply attaching hearts with the full awareness that all will eventually go back into the ground. The meaning is not in spite of the impermanence. I think it is, at least partially, because of it. It is because we know that everything we care about is temporary, that it becomes worthy of our full presence, attention, and being while we have it.

We have it. Right now.

We’ve lost some of it already. What do we need to be present to in this moment? And what do we need to mourn and bury?

In the children’s garden at the hospital.

Fairness and Deservedness

I had an epiphany the other day in supervision at work. I’m at the beginning of a 12 month residency as a chaplain and my days are full of tragedy and self-evaluation. I was talking about the heartbreak of experiencing how unfair it is that the poor are poor. And my supervisor was like, well, do you think Jeff Besos deserves his billions? And I said, of course not! We both exploded with laughter. And it suddenly became crystal clear that no one deserves what they have, whether it’s that they have way too much or not nearly enough.

Read MorePhoto cred: https://www.superherohype.com/movies/490905-wonder-woman-1984-review-indulging-and-condemning-80s-excess

False Choices

Why do we insist that women have to choose between love and ambition? I cannot tell you how many times I’ve perceived that choice as being either/or. I remember when I was working at a non-profit while pregnant with Macy and my female colleagues talking about how women can have it all but not all at the same time. Women tell each other that our time will come later. Or when I was a primary caregiver married to a minister, I received a lot of praise for my decision to work from home. We often want women to fulfill the role of being the emotional and logistical support for every member of the household, even the damn pets, before she can pursue her own dreams and ambitions…

Read MoreMy porch pumpkins this year. Because they make me really happy.

What are you doing tonight?

I’ve been doing a lot of personal, emotional work during the pandemic. Not because I’m so brave and ambitious necessarily. It just seems that my growth requires a good look in the mirror these days. One of the things that came up for me in CPE was an understanding that I don’t have a deep relationship with certain emotions, namely fear. Because I downplay my own fears, I also tend to downplay the fears of others. That’s not such a great habit for an aspiring hospital chaplain. Turns out, fear is a really important human emotion.

Read MoreOur other socially-distant stomping grounds from this summer since we don’t take pictures at the Y

Floating

I have a thing about floating. Obviously, a lot of people do or they wouldn’t have those awesome float places. As a sensitive person, sensory deprivation is really good for me from time to time. The girls and I have been swimming once a week at the Y all summer. A lot of our summer rhythms had to be re-thought with COVID in mind. I’ve been surprised at how much joy and rest that hour has come to provide through all the turmoil that is 2020. Cue the memes.

Read MoreBlurry picture of me post-nap.

Reprogramming a Personal Faith

I don’t know about y’all, but pandemic life is putting me in the position of looking in the dark nooks and crannies of my soul. It seems as if there are some piles of old hair and dust that need to be swept out of my subconscious and apparently, the time is now…

Read MoreIntent is No Longer Enough

I’ve written quite a bit on here about my value of assigning positive intent in my relationships. It has helped me so much in my marriage, with my relationship with feedback, and in my journey towards self-kindness. It’s been in my peripheral vision for some time now that impact is different than intent and that impact also matters. But it’s finally clicking this week, with everything happening culturally around the inherent dignity of black lives, that impact is actually a higher rubric than intention. It is my new goal to take responsibility for my impact while holding necessary space for my intention. I can hold space within myself to validate a good intention while still taking public responsibility for a harmful impact.

This space, my blog, has been a wonderful way for me to share my faith deconstruction experience, learn to tune into my own voice, and to express my anger, which was an emotion I had blocked within myself (I think this is common for evangelical women). The impact has been largely positive. However, the impact has not been only positive. I have written posts that have hurt people, ended relationships, and created lasting impacts in my personal life. And while I think sometimes pain leads to growth (hello our current racial justice tension - this is the way forward towards systemic change), it does not mean that people who were just going about their lives found themselves being called out by me publicly appreciated my writing about them. I understand that part of writing in public inevitably creates some negative reactions, but I also want to take responsibility for the impact I’ve made that has been harmful.

I certainly don’t want to link the posts that created harm here, but I do want to name people who I have harmed in my writing. I want to apologize to Ben Cook, Billy and Brenda McKenzie, and Kristi Belt for any harm my writing caused you. The impact of my self-expression in your life has not exactly been life-giving. And for that, I am sorry.

It’s amazing how long some things take to click in my mind. I think that might be just how learning works. But I’d rather apologize really late than not apologize at all. I’m truly sorry for hurting you.

George Floyd. Taken from Shaun King’s Facebook page.

Pentecost - Speaking Truth to Power

The world is on fire, friends. We’re living in a global pandemic. Black men are being kneeled on to their deaths. Our cities are burning. Our economy is crashing. People are hungry. And scared. And angry. This is our reality. The question is not “why can’t we all just get along?” That is a white question. The question is, for us white folks, “what the hell are we gonna do about it?” This is not the time to ask our black brothers and sisters to do our emotional labor. This is a time to stand in between them and the police. This is a time to speak truth to power. If our police are not breaking rules while they stand on black necks, the rules have got to change. Period.

The Holy Spirit is a woman. I’m sure of it. Hell, she’s probably a black woman. Today is the day the Christian church celebrates and worships the Spirit who raised Jesus Christ from the dead. She put little embryo Jesus into young Mary’s womb. She created the world alongside her Trinity partners. She is no slouch. And she is what wells within us when we speak truth to power. She is the Spirit of disruption when systems are unjust. The Holy Spirit of God is not here to placate my white fragility. She is the voice that calls me to question my motives, my fear, my silence.

The events in our country this week, specifically the murder of George Floyd, should cause every white person in this country, especially white Christians who believe in the sanctity of life, to look in the mirror and ask, “What can I do?” “What do I need to learn?” “How am I complicit in his death?” And then GET. TO. WORK.

I decided not to post an image of George’s death. There was a time in my process of looking at my white privilege where I shared images of violence against people of color and forced myself to watch the videos of the deaths of Tamir Rice, Eric Garner, and Philando Castile in order to wake myself up to the reality of the black experience. That is important. If you have not exposed yourself to the material that exists of these moments and find any hesitation within yourself to speak out, watch the videos. You need to. But I also know that black people have seen enough of this footage to hold the trauma in their DNA. Generations, hundreds of years of oppression lives in their very cells. So I will not post that here. It is available for you to see. Instead, I chose to put an image of George when he was alive and healthy. I got it from Shaun King’s Facebook page (he’s a great social media follow if you’re looking to learn).

If you believe in the Holy Spirit and celebrate her power and beauty this year on Pentecost, I ask that you beg her to tell you what to do today in response to George’s life and death.

There is no peace without justice. May we do the work to enjoy the peace we all desire.

Selfie on my first 12 hour night shift.

To Be a Witness

A huge part of chaplaincy work is witnessing people in the midst of the hardest moments of their lives. It is one of the most interesting, devastating, and humbling parts of the job for me. It also means that the illusion of safety and fairness that most adults live in so as to carry on in the world is largely refuted every time I come to work. I tend to take risks under the premise of “what are the odds that x, y, and z will actually occur?” Well, in the hospital setting, I am regularly confronted with the exception to those odds. I’m spending time witnessing a mother whose baby did drown in the bathtub or the spouse whose husband did commit suicide. It’s harder to maintain my self-imposed delusions that I live in a world where I can control the outcomes of circumstances related to the people and things I care about most. It is its own form of unraveling.

I am regularly overwhelmed by the tragedy of the human experience. I know my lens right now is specific to hospital work in a pandemic, but some really shitty things happen in the world. It can be so horrific to play my part as witness. There is no way to be a witness and remain disengaged, nor should I remove myself emotionally even if I could. The purpose of the witness is to hold space, document, reflect, and create a sense of solidarity in the horror of what is happening. And while the patient or the patient’s family is in fact living their own story and I am living mine, the intersection of my story with the stories of the suffering day in and day out creates a level of vulnerability and fatigue that has changed me in a real way. Not in a traumatic way or in a way that I think I would regret, but there is a way of navigating the world without really knowing and seeing the depth of what is possible in a moment of freak miscalculation or accident. I will never go back to that space of not knowing. And while that means I am operating without as many protective illusions about life and safety and fairness, it also means that I am holding gratitude and deep appreciation for what is. What I have, what I may lose, who I come home at the end of the day. As cheesy as it sounds, all I have is now. And I am infinitely blessed.

I’m still working out my theology of suffering. I know that the “everything happens for a reason” and “God’s plan includes this” kinds of frameworks do not work for me. I personally cannot navigate a world of suffering with the idea that God approves it all or that suffering is okay. I absolutely cannot. I do believe in a God of redemption and restoration. I believe in a God who does care for humanity collectively and personally. But shit happens and it happens lethally and unfairly. That is a hard thing to witness every single day. There is so much in this hospital system and in the realities of life that are not mine to hold or fix. But this much I know. I can be a witness and I personally can only do it through faith.

CPE - A Marathon of Unraveling

I had a friend ask recently how things were going for me at the hospital. For those of you who don’t know, I am almost done with a unite of CPE (Clinical Pastoral Education) that began right as everything shut down because of COVID-19. That means I started a full-time unpaid job at a hospital in the final weeks of my master’s program in the middle of a global pandemic. I’m weird. My kids’ first day home from school was my first day at work at the hospital. My graduate degree is done now (Yea!) and I’m closing in on my final weeks of CPE. It’s weird to think about what it will be like when all of this is done as the job I planned to return to for the summer at the Y probably won’t be up and running still. Eh, if anything COVID-19 has taught me is to just plan on today. I’ll think about that later.

Everyone I talked to before starting CPE who had done it themselves described it as “intense.”* I thought I was well-suited for the work because I’ve done a lot of personal work and therapy and have a disposition for connecting with strangers. Turns out, that’s all true. AND my work is ongoing. Like, some of it is just beginning. The difference between chaplaincy and other spiritual or counseling work is that the chaplain’s presence IS the intervention, which means the chaplain must connect to their own emotions and story in order to engage the person at their point of need (rather than meeting their needs). We do not provide guidance and information. We go into the valley where the patient is and engage the feelings of what that’s like. We do not escort people out of their valley nor do we skirt around the valleys we’d rather avoid. This means my story is regularly activated and I have to care for myself as I stay present with people in sometimes the hardest moments of their lives. I’ve seen some real shit, you guys. So. Many. Hard. Things. This means I cry at work. This means I’m sometimes triggered by interactions. There is no “fixing” things or experiences for others. I cannot and will not rob others of their work to do. It is their story. Our stories just cross paths for a moment. I am an enneagram 2 called to witness the human experience and not fix it. I’m called to engage the pain and tragedy of what it is to be a human being.

In this process, I have experienced a beautiful unraveling. I’m shedding narratives about myself that are no longer serving me and I’m realizing what I can and cannot do. It’s an experience in exploring my own spiritual authority and allowing my intuition to participate actively while keeping my personal curiosity in check. It’s an experience in examining all my relational and emotional patterns. It’s unblocking certain feelings and experiences I haven’t attended to or receiving feedback from my peers about things I don’t know about how I come across to others. It’s bringing myself to the table of engagement without making the moment about me. My story becomes in service to theirs. I’m discovering the types of encounters I really enjoy (post-partum moms with their babies) and the ones that require a shit ton of care after (turns out, code blues aren’t as sexy as I’d anticipated).

It’s coming into a patient’s life for just a moment in the hopes of providing transitional care and shoring up their support systems for their long-term work. In some ways, my scope of practice is small. Most patients I only see one time. But I like to think that just having someone hold space for your reality in the midst of a traumatic experience can help lessen the work leftover when the trauma has passed. It also means that my role can be as a conduit for someone to practice their faith the way they prefer, which can be totally different from the way I practice mine. So sometimes I get to be a part of someone connecting to their spiritual leader or to words and methods of prayer or meditation I’ve never experienced in my tradition or even my religion. It’s an incredible honor to be that link. I really love it when I get to do that. One time I got to stand in for a Catholic priest (visitation for them is limited to end of life circumstances) and rather than activating my semi-regularly present impostor’s syndrome, I felt ELATED by it. My Catholic grandparents were with me with my arm raised above my precious friend who requested a blessing.

I don’t know what’s next for me. I feel like I have so many emotional internet browser “tabs” open right now, so many things I need to work on within myself. And plenty of shifts to cover and Zoom meetings to attend. But in the midst of this tornado, I’m being reborn. I’m growing. I’m coming into my calling. I’m being integrated into a more mature, authoritative version of myself.

* In case you’re unfamiliar with the process, CPE is done in units of 12 weeks of work. If you’re lucky enough to get a residency (my long-term goal), you can do 4 units consecutively and get paid. I’ve almost completed an internship at Legacy Emanuel in Portland, which will give me one unit. I can’t do a ton with one unit, though many places hire someone with 2. CPE involves shift work, classes, supervision, reading/writing, group work, and mentoring. I’ve got mainly 12 hour overnight shifts where I’m the only chaplain there for an adult hospital, children’s hospital and the Oregon Burn Center. It’s over 550 beds. I go to all the codes, deaths, attend to requests for spiritual care, and round on all our trauma admits. I pray with people pre-surgery, assist patients and their families with naming feelings, sifting through their experience in the hospital and what brought them to us. I attend to families who have lost a family member. I help people fill out an Advance Directive (including things like a DNR). I’ve sat with a lot of people who were on the brink of death, including infants. I help people pick out funeral homes and figure out how to honor their dead in the midst of a pandemic. The work is varied. I never know what’s on the other side of that door. The 12 hour overnight shifts are covered by interns every night for the whole 12 weeks, so on the days we have class, one of us was always on the night before and one of us is always on the night after. It’s a fascinating experiment in what the human body and heart can handle.

Photo cred: Pinterest

Maundy Thursday - Huh

It seems fitting to me that this is the first year I have participated in my church’s Maundy Thursday service (of course, on Zoom). If you haven’t ever included this Holy Day in your spiritual practice, it is an commemoration of Jesus’ last day before his crucifixion. We take communion and we tell the story of his death. Then we regather on Easter morning to break the vigil we begin on Maundy Thursday to celebrate the resurrection of Christ.

I say it seems fitting because this year, death feels close. Thankfully, I am not ill. None of my loved ones are ill. And I know that makes me incredibly privileged during this time of COVID-19, where the virus seems all around us. But between the virus and my CPE work at the hospital, it seems I am daily being confronted with the reality of death.

It has become part of my spiritual practice to attend to the dead and dying and their loved ones. This is new work for me. I have not been around a lot of death, though I spent my childhood in community and we certainly lost many people over the years. Somehow, being in those hospital rooms, especially with such limited visitation right now, this feels different.

For one, I am witnessing it almost every day I come into work (this is not a reflection of the state of the virus, but I think a common experience in Spiritual Care practice). That’s a lot of death. And now today, I spent a bit of my evening singing and reading the story of the death of God.

There’s a true heaviness to this time and to the work of God in the world sometimes. It is not all light and breezy. And for me, it has become important practice to not wish the heaviness away (I don’t mean to never take a break, but rather to not play ‘hot potato’ with it). This work, this deep, deathly work is important to what it means to be a human being. It’s hard. There are a lot of feelings to experience: fear, sadness, grief, anxiety, anger, resentment, frustration, stress…I could name every feeling and it it probably applies in the roller coaster experience that is death.

One of my fellow CPE interns recently said, “There’s no more human thing to do than to die.” And I thought, “That would not have been something I would have subscribed to three months ago.” This is a specific season, a specific time - both in the world and in our lives.

And I guess I wanted to come on here tonight and just wish peace and love to everyone as we communally go through death both in the Holy Week that is Easter and in the experience of COVID-19, where so much is left feeling uncertain and unstable. I think in all the instability and loss, we can find God here. I think he can meet us here. He can be present with us in this.

I don’t subscribe to any idea that God brings suffering or inflicts it deliberately. What a cruel thing to believe. I believe in love. And you know what? Love meets us in suffering. That’s why loss hurts so much in the first place - it’s the evidence that we experienced love at all. Glennon Doyle calls it our receipt. Embrace the pain of loss and hold on tight. There is beauty and growth waiting for us in the pain. Not when all the pain goes away - right now, in the pain.

And if this isn’t the right message for you tonight, if you need something happier and more shiny, it’s okay to skip me this time. I totally understand how important it is to guard our consumption of material right now. But if you’re feeling the heaviness, I just want you to know, that’s what makes you human. And humans do hard things. You are loved. Easter Sunday is coming.